The tabr tutorials began with a basic example that

introduced the general workflow.

- Define a musical phrase with

phrase()or the shorthand aliasp(). - Add the phrase to a

track(). - Add the track to a

score(). - Render the score to pdf with

tab()or anotherrender_*function.

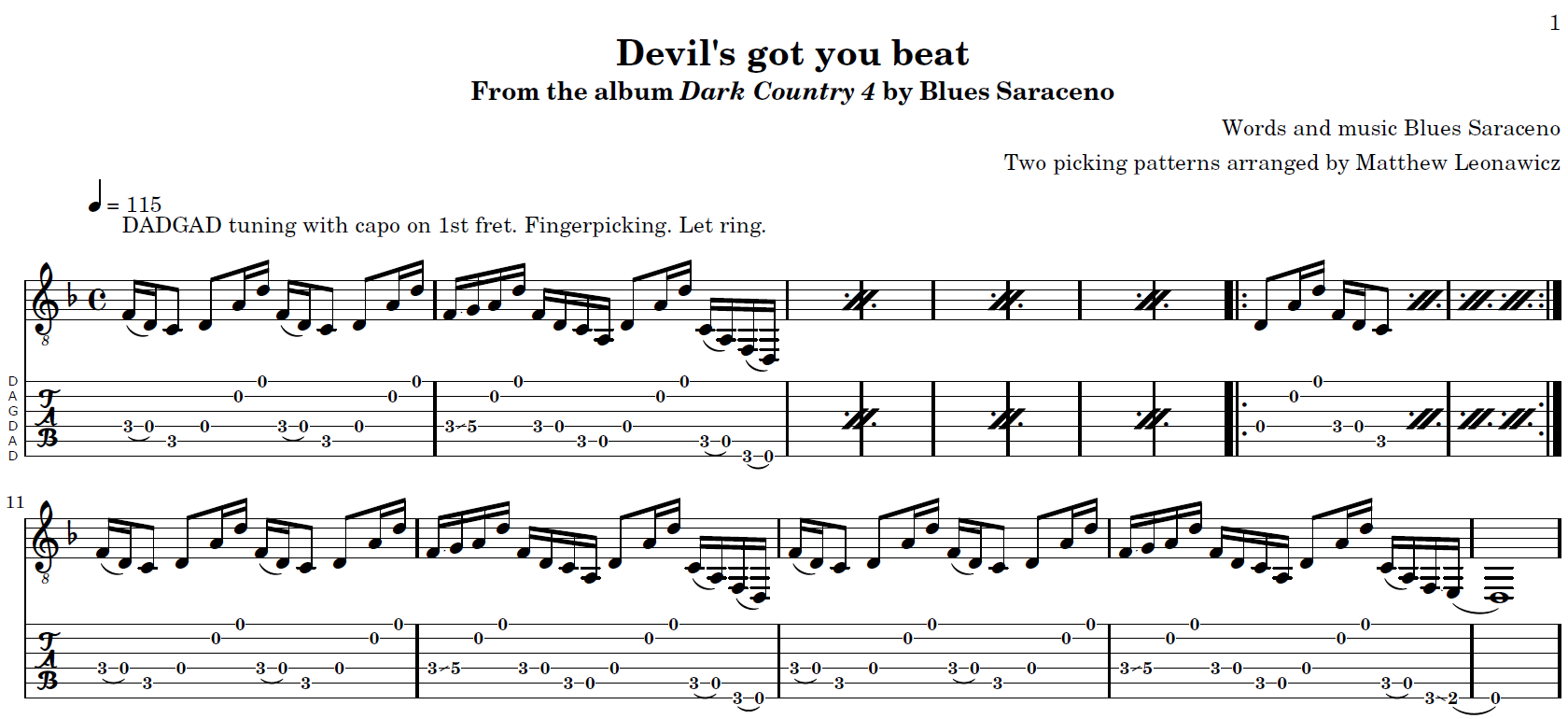

This short R script example is more complex. It does not represent a complete tab of a song; it is just a short arrangement of two basic fingerpicking patterns similar to but not exactly the same as heard in Blues Saraceno’s Devil’s got you beat. The second pattern is actually just a small slice of the first pattern that is shifted in time slightly. While not a complete tab, it is much more thorough than the opening tutorial example, making use of several techniques and functions that have been covered.

Some of the most interesting things to note below include:

- Non-standard tuning (DADGAD) plus a capo on the first fret.

- Use of all the available song information arguments in

header. - Nested repeats with percent repeats applied inside of a volta repeat.

- Avoidance of repetition of the text annotation attached to the opening note when using percent repeats.

R code

header <- list(

title = "Devil's got you beat",

composer = "Words and music Blues Saraceno",

performer = "Blues Saraceno",

album = "Dark Country 4",

subtitle = "From the album Dark Country 4 by Blues Saraceno",

arranger = "Two picking patterns arranged by Matthew Leonawicz",

copyright = "2016 Extreme Music"

)

txt <- c("DADGAD tuning with capo on 1st fret. Fingerpicking. Let ring.")

tuning <- "d, a, d g a d'"

# melody 1

notes <- c(pn("f d c d a d'", 2), "f g a d' f d c a,")

info <- purrr::map_chr(c("16(", notate("16(", txt)),

~pc(.x, "16) 8 8 16 16 16( 16) 8 8 16 16 16- 16*7"))

strings <- "4 4 5 4 2 1 4 4 5 4 2 1 4 4 2 1 4 4 5 5"

p1 <-purrr::map(info, ~p(notes, .x, strings))

e1 <- p("d a d' c a, f, d,", "8 16 16 16( 16) 16( 16)", "4 2 1 5 5 6 6")

e2 <- p("d a d' c a, f, e, d,", "8 16 16 16( 16) 16- 16( 1)", "4 2 1 5 5 6 6 6")

#melody 2

p2 <- p("d a d' f d c", "8 16*4 8", "4 2 1 4 4 5")

p_all <- c(pct(c(p1[[2]], e1), 3), volta(pct(p2, 3), 1), p1[[1]], e1, p1[[1]], e2)

track(p_all, tuning = tuning) |> score() |>

tab("out.pdf", "dm", "4/4", "4 = 115", header)You can see above that notate() can often obstruct

otherwise convenient opportunities for code reduction. Avoiding

repeating the annotation means avoiding repeating whatever it is bound

to. This is not a problem for percent repeats because there is nothing

to show, but would be for the repetitions of the melody at the end of

the score. This is why info was mapped to a length 2 vector

using an opening note with and without a bound text annotation,

respectively.

The e1 and e2 endings on the phrase

p1 were not used as default and alternate endings in a call

to volta(), respectively, because they would fail the bar

check; p1 alone does not end at the end of a measure, but

rather lasts for a measure and a half. This example also shows how a

single note difference at the very end of the second ending,

e2, an ending that is only played once at the end of the

arrangement, is enough to stop you from defining what would sensibly be

the full phrase (p1 through e1) as such. The

slightest change forces you to split things up and expand the code, just

like in a tab. And most music, at least the kind for which there is any

point in transcribing, is going to change things up often even for

repeated sections.

Result

The result of the call to tab() is as follows.

The next example refactors the phrases above to properly represent multiple voices in the output.