Overview

This section goes into deeper detail on building musical phrases out of individual notes using the syntax available for phrase construction. It also describes how to add note information to the notes in a phrase.

As mentioned in the last section, “phrase” in tabr does

not require a strict definition. It is recommended to keep phrases short

enough that they do not too much cognitive load. They should also

represent meaningful or convenient segments of music, for example whole

measures, a particular rhythm section, or an identifiable section of a

longer solo.

Writing music notation in R code is not intended to replace LilyPond

markup. You can always write LilyPond markup directly and this will give

you more options and greater control. The motivation for

tabr is primarily music data analysis from a notation

perspective, but to the degree that various types of notation are

supported, it also allows you to transcribe your data to sheet music or

tablature. Working from a programming language like R is also very

different from writing static markup files. While the API is far more

limited than writing LilyPond markup directly, generating music notation

programmatically and creating sheet music dynamically is an entirely

different use case from writing markup for a specific song.

The opening section showed a basic example using a single, and very simple, phrase. This section will cover phrases that include notes and rests of different duration, slides, hammer ons and pull offs, simple string bends, and various other elements. Phrases will become longer and more visually complex. There is no way around this fact. But with proper care they can be kept manageable and interpretable, depending on your comfort level with music theory, notation and R programming.

Before diving in, take a look at the tables below for an overview of some common syntax and operators that are used throughout this section.

<!-- KNITR_ASIS_OUTPUT_TOKEN --><table class="table table-striped table-condensed" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;">

<caption>tabr::tabrSyntax</caption>

<thead>

<tr>

<th style="text-align:left;"> description </th>

<th style="text-align:left;"> syntax </th>

<th style="text-align:left;"> example </th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> note/pitch </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> a b ... g </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> a </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> sharp </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> # </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> a# </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> flat </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> _ </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> a_ </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> drop or raise one octave </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> , or ' </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> a, a a' </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> octave number </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 0 1 ... </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> a2 a3 a4 </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> tied notes </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> ~ </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> a~ a </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> note duration </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 2^n </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 1 2 4 8 16 </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> dotted note </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> . </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 2. 2.. </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> slide </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> \- </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 2- </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> bend </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> ^ </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 2^ </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> muted/dead note </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> x </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 2x </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> slur/hammer/pull off </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> () </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> 2( 2) </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> rest </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> r </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> r </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> silent rest </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> s </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> s </td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="text-align:left;"> expansion operator </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> \* </td>

<td style="text-align:left;"> ceg\*8, 1\*4 </td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

<!-- KNITR_ASIS_OUTPUT_TOKEN -->There are additional single-note articulations that can be specified,

such as accented or staccato notes. This can be provided using the name

in square brackets, e.g., [accent] or

[staccato]. In special cases an abbreviated syntax is

available, e.g., -^ or -.. There are many

options. Some of the most common ones are shown. See the

articulations dataset.

head(articulations)#> type value abb

#> 1 standard accent ->

#> 2 standard espressivo <NA>

#> 3 standard marcato -^

#> 4 standard portato -_

#> 5 standard staccatissimo -!

#> 6 standard staccato -.Notes

The first argument to phrase() is notes.

Notes are represented simply by the lowercase letters

c d e f g a b.

Sharps and flats

Sharps are represented by appending # and flats with

_, for example a# or b_. In

phrases and the various tabr functions that operate on

them, these two-character notes are tightly bound and treated as

specific notes just like single letters.

Space-delimited time

A string of notes is separated in time by spaces. Simultaneous notes

are not. For example, "a b c" represents a sequence of

notes in time whereas "ceg" represents simultaneously

played notes of a C major triad chord. For now the focus will remain on

individual notes. The end of this section includes a tiny chord example.

Chords are discussed in more detail in later sections.

Functions in tabr also handle vector-delimited time. It

is not as quick to type out the example below as a vector of notes, but

if you already have a vector you do not have to collapse it. Package

functions will accept either timestep format.

Unambiguous pitch

While it is allowable to specify note sequences such as

"a b c", this assumes the default octave (number 3), the

one below middle C. But this may not be what you intend. In the example

here, you might mean the consecutive notes "a2 b2 c3" or

a3 b3 c4.

Combining the note and the octave number specifies the absolute

pitch. LilyPond markup uses single or multiple consecutive commas for

lower octaves and single quote marks for higher octaves. This notation

is permitted by tabr as well. In fact, if you specify

integer suffixes for octave numbering, phrase() will

reinterpret these for you. The following are equivalent, as shown when

printing the LilyPond syntax generated by phrase().

The second example here also shows the convenient multiplicative

expansion operator * that can be used inside character

strings passed to the three main phrase() arguments. Use

this wherever convenient, though this tutorial section will continue to

write things out explicitly for increased clarity. Other operators like

this one to help shorten repetitive code are introduced later.

phrase("c1 c2 c3 c4 c5", "1 1 1 1 1") # not recommended#> <Musical phrase>

#> <c,,>1 <c,>1 <c>1 <c'>1 <c''>1

phrase("c,, c, c c' c''", "1*5") # recommened format#> <Musical phrase>

#> <c,,>1 <c,>1 <c>1 <c'>1 <c''>1In tabr the two formats are referred to as integer and

tick octave numbering. Note that octave number three corresponds to the

central octave (no comma or single quote ticks) with the tick numbering

style. This is why the 3 can be left off when using the

numbered format. c3 corresponds to the lowest C note on a

standard tuned guitar: fifth string, third fret.

For more extreme octaves, the latter style requires more characters.

However, some may find it easier to read for chords like an open E minor

"e,b,egbe'" compared to either "e2b2e3g3b3e4"

or "e2b2egbe4". Regardless, integer octaves are not

recommended, the primary reason being that they limits functionality.

Numbers are used for indicating time (music class objects).

Therefore, integer octave format can only be used in simple strings and

phrases, not in more complete objects. The tick format also matches that

used by the LilyPond software. For multiple reasons, just use tick

format. The rest of the vignettes stick to tick format except when

making some other specific comparisons.

Time: the essential note metadata

Additional information about a note is passed to the second

phrase() argument, info. This enables removing

ambiguities other than the pitch itself. For the moment, only time

duration is introduced. A brief diversion from the info

argument follows in order to cover rests, tied notes, and string

specification; three important elements that can be described with

phrase(), but which are not actually passed via the

info argument. Afterward, focus returns to

info with more detailed coverage of the various note

metadata that is supplied to phrase() via

info.

Duration

The most basic, and always required at a bare minimum, is the time

duration of each note. Notes always have duration. The previous example

showed a string of ones, info = "1 1 1 1 1", of equal

length (in terms of space-delimited entries in the character string) to

the first argument giving a sequence of five C notes from different

octaves. These ones represent whole notes, lasting for an entire measure

of music. Other possible integer values are 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64,

though most users probably won’t have reason to go beyond 16. The

possible integers represent whole notes, half notes, quarter notes,

eighth notes, sixteenth notes, etc.

The format is technically specifying the denominator. You might be

inclined toward 1, 1/2, 1/4, etc., since the durations represent

fractions of a single measure, not a total number of measures. This

denominator shorthand where the implicit numerator is always one saves

typing, but is also consistently with LilyPond itself. Below is an

example using different durations. Entire songs are much longer and more

complex and do not meaningfully benefit from piping, but for this and

other short examples that follow, it is convenient so it will be used.

Other arguments in tab are not relevant yet so for now just

accept the defaults.

Rests and ties

Rests and tied notes are actually part of the note

argument. Both have duration, which is what belongs in

info.

Rests are denoted by "r". In general, string

specification is irrelevant for rests because nothing is played, so you

can use a placeholder like x instead of a string number

(see next section on string numbers). For the moment this example is not

specifying the optional argument, string, so this can be

ignored. Replacing some notes in the previous phrase with rests looks

like the following.

At first glance, tied notes might seem like something that ought to

be described via info. Even though the second note is not

played, a tied note is still distinct from the note to which it is tied

as far as notation is concerned.

For example, when tying a note over to a new measure, it must be

included twice in notes. The tie is annotated on the

original note with a ~ as follows.

The note is played once and has a duration of one and a quarter measures, but is still annotated as one quarter note tied to one whole note.

Explicit string-fret combinations

Specifying the exact pitch is still ambiguous for guitar tablature because the same note can be played in different positions along the neck of a guitar. Tabs show which string is fretted and where. For example, in standard tuning, the same C3 note can be played on the fifth string, third fret, or on the sixth string, eighth fret. If left unspecified, most guitar tablature software will attempt to guess where to play notes on the guitar. This is not done by some kind of impressive, reliable artificial intelligence. It usually just means arbitrarily reducing notes to the lowest possible frets even if a combination of notes would not make sense or be physically practical for someone to play them that way.

There is one degree of freedom when the note is locked in but its

position is not. It is not necessary to specify both the string number

and the fret number. Providing one implicitly locks in the other. If you

know the pitch and the string number, the fret is known. LilyPond

accepts string numbers readily. To isolate these numbers from the

info argument notation in phrase(), they are

provided in the third argument, string, which is also

helpful because string is always optional.

Returning to the earlier phrase, without the rests, the equivalent

phrase with explicit string numbers would have had

string = "5 4 4 4 3 3 2 2 2 2". The second version with

rests could have been provided as

string = "x 4 4 x 3 x 2 x 2 x". Instead, play further up

the neck beginning with C3 on the sixth string, eighth fret.

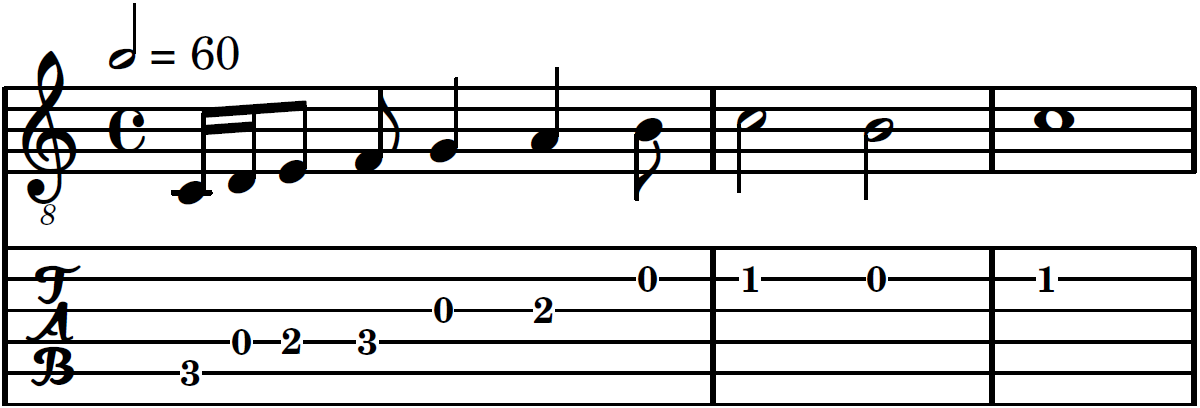

notes <- "c d e f g a b c' b c'"

info <- "16 16 8 8 4 4 8 2 2 1"

strings <- "6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 4"

phrase(notes, info, strings) |> track() |> score() |> tab("ex04.pdf")

Some programs like LilyPond allow for specifying a minimum fret

threshold, such that every note is played at that fret or above. This

would work better for some songs than others of course. It is still not

as powerful or ideal as being explicit about every note’s position. This

threshold option is not currently supported by tabr. It is

recommended to always be explicit anyway, as it leads to more accurate

guitar tablature. There is a preponderance of highly inaccurate guitar

tabs in the online world. Please do not add to the heap.

Note metadata continued

This section returns to the info argument to

phrase() with more examples of various pieces of note

information that can be bound to notes.

Dotted notes

Note duration was introduced earlier, but incompletely. Dotted notes

can be used to add 50% more time to a note. For example, a dotted

quarter note, given by "4.", is equal in length to a

quarter note plus an eighth note, covering three eighths of a measure.

Double dotted may also be supplied. "2.." represents one

half note plus one quarter note plus another eight note duration, for a

total of 4 + 2 + 1 = 7 eighths of a measure.

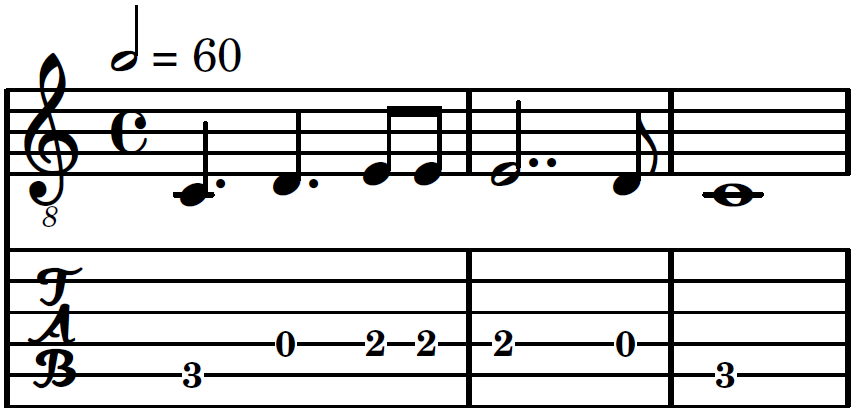

A couple measures with no rests that contains dotted and double dotted notes might look like this.

Dots are tightly bound in dotted notes. tabr treats

these multi-character time durations as singular elements, just as it

does for, say, sixteenth notes given by a "16".

Staccato

Notes played staccato are specified by appending a closing square

bracket directly on the note duration, e.g., altering "16"

to "16]". This will place a dot in the output below notes

that are played staccato.

Muted or dead notes

Muted or dead notes are indicated by appending an "x" to

a note duration, e.g., "8x".

Multiple pieces of information can be strung together for a single

note. For example, combining a muted note with staccato can be given as

"8x]". In this early version of tabr, do this

with caution, as not all orderings of note information have been

thoroughly tested yet. Duration always comes first though. Some pieces

of information are not meant to go together either, such as a staccato

note that must essentially be held rather than released, for the purpose

of sliding to another note. Use human judgment. If you don’t ever see

something in sheet music, it may not work in tabr

either.

In this case, the example will work with "8x]" or

"8]x". In fact, even accidentally leaving an extra staccato

indicator in as "8]x]", which does undesirably alter the

output of phrase(), will still be parsed by LilyPond

correctly. Nevertheless, stick closely to patterns shown in these

examples if possible.

Slides

Slides are partially implemented. They work well in tabr

when sliding from one note to another note. Slides to a note that do not

begin from a previous note and slides from a note that do not terminate

at subsequent note are not implemented. This is usually done with a bit

of a hack in LilyPond by bending from or to a grace note and then making

the grace note invisible. This hack or some another approach has not

been ported to tabr.

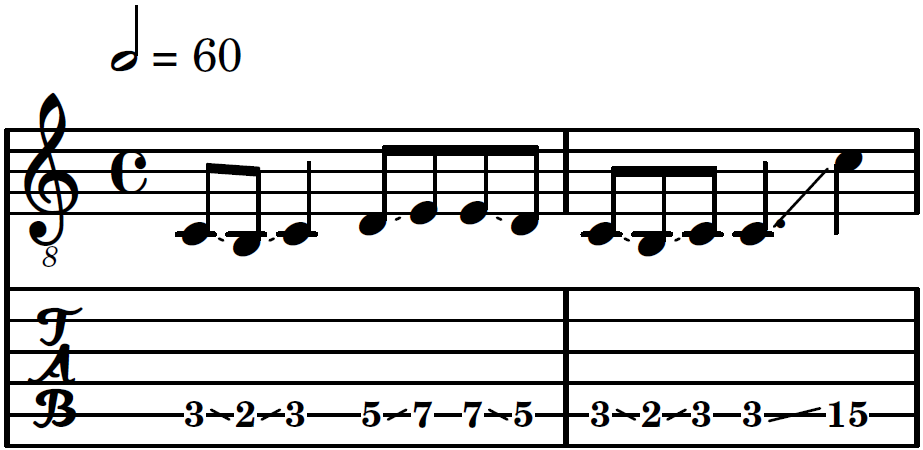

phrase("c b, c d e e d c b, c c c'", "8- 8- 4 8- 8 8- 8 8- 8- 8 4.- 4", "5*12") |>

track() |> score() |> tab("ex08.pdf")

As a brief aside, note the use of * above in the

string argument to reduce typing. It is necessary to

specify string here in order to ensure the notes are all on

the fifth string in the output. Any space-delimited elements in

phrase() can take advantage of this terminal element

notation for multiplicative expansion of an element. Terminal means that

it must be appended to the end of whatever is being expanded; nothing

can follow it. c*4 a*2 expands to c c c c a a

inside phrase(). 4.-*2 is replaced with

4.- 4.-. This convenient multiplicative expansion operator

within character strings passed to phrase() is available

for the notes, info and string

arguments.

Hammer ons and pull offs

Hammer ons and pull offs use the same notation and are essentially

equivalent to slurs. They require a starting and stopping point.

Therefore, they must always come in pairs. Providing an odd number of

slur indicators will throw an error. The beginning of a slur is

indicated using an open parenthesis, (, and the end of a

slur is indicated with a closing parenthesis, ).

Editing the previous example, change some of the slides to hammer ons and pull offs.

- Change the opening two slides (C to B to C) to use a pull off

followed by a hammer on. Note that each must be opened and closed, hence

the

)(appended to the B, the second eighth note. Using only a single set of parentheses, opening on the first note and closing on the third, would make a single, general slur over all three in the output. - Next, hammer on from D to E, pick E, and pull off back to D. Notice the notation is identical for in both directions. Whether the slur between the two consecutive notes is a hammer on or pull off is implicit, given by the direction.

- Then play the C-B-C part again, but differently from the opening. Pick, pick, hammer on, pick, and then the final slide.

- Finally, transpose up one octave by increasing the octave numbers

attached to the pitches in

notes. The reason for this is simply to demonstrate the placement of slurs above or below notes on the tablature staff depending on the string number. With this transposition, move from the fifth to the third string.

notes <- pc("c b, c d e e d c b, c c c", "c' b c' d' e' e' d' c' b c' c' c''")

info <- pn("8( 8)( 4) 8( 8) 8( 8) 8 8( 8) 4.- 4", 2)

strings <- "5*12 3*12"

phrase(notes, info, strings) |> track() |> score() |> tab("ex09.pdf")

Another brief aside: tabr has some helper functions that

make your work a bit easier and your code a bit more legible, ideally

both. Using meaningful separation helps keep the code relatively

readable and easier to make changes to when you realize you made a

mistake somewhere. Don’t write one enormous string representing an

entire song. Aside from the avoiding code duplication where there is

musical repetition, even something that might not repeat such as a

guitar solo still benefits greatly from being broken up in to manageable

parts.

pc() is used above to combine both parts fed to

notes rather than write a single character string.

pc() is a convenient function for joining strings in

tabr. It maintains the phrase class when at

least one element passed to pc() is a phrase object. The

string passed to info does not change between parts so it

can be repeated. Using the *n within-string operator from

earlier does not apply here, but another function similar to

pc() is pn(). It repeats a phrase

n times.

String bending

String bends are available but currently have a limited

implementation in tabr and bend engraving in LilyPond

itself is not fully developed. Specifying all kinds of bending, and

doing so elegantly and yielding an aesthetically pleasing and accurate

result, is immensely difficult. Bends are specified with a

^. Bend engraving does not look very good at the moment and

control over how a bend is drawn and any associated notation indicating

the number of semitones to bend is currently excluded.

In the example below, a half step bend-release-bend is attempted over

the three B notes shown at the end of the first phrase. Because the

string is only plucked one time, the first two B notes are tied through

to the third. Since a tied note is a note, this is done in

notes. The two bends are indicated with ^ on

the first and third notes via info. A similar approach is

taken with the second phrase, although with full step bends from G to A.

In both cases, the initial bend is not a pre-bend, but should be very

quick. None of these fine details can be provided with the current

version of tabr.

notes <- pc("r a, c f d a f b~ b~ b", "r a c' d' a f' d' g'~ g'~ g'")

info <- pn("4 8*6 16^ 16 2..^", 2)

strings <- pc("x 5 5 4 4 3 4 3 3 3", "x 4 3 3 4 2 3 2 2 2")

phrase(notes, info, strings) |> track() |> score() |> tab("ex10.pdf")

As you can see, the implementation is limited in tabr.

It is also relatively difficult to achieve natively in LilyPond. The

bends are different but the number of steps must be inferred from the

key. The timing of bends and releases is challenging. The engraving is

poor. But it is a start point.

Chords

Chords are covered in detail in later sections. For now, a brief

example is given to more fully demonstrate the concept of

space-delimited time and the use of simultaneous vs. sequential notes in

tabr. The example below shows how to include some open C

major chords inside notes. It is simply a matter of

removing spaces. The tightly bound notes are simultaneous in time.

info applies to the entire chord because it describes

attributes of notes played at a given moment. There are obvious

limitations to this though fortunately not hugely detrimental.

string numbers are tightly bound for chords as well.

It can be seen above that just like individual notes, chords can be

specified using any combination of tick or integer octave numbering.

They are equivalent. Tick style may be more readable for some. More

importantly, remember that numbered octave format restricts other

functionality. Octave 3 is the implicit default and can be left out.

Note the shorthand string numbering. Note info and string numbers can be

recycled across the timesteps in notes as long as their

length is one.

When a single string number is given for a timestep, but there is more than one note at that timestep, it is assumed to be the starting string number and addition consecutive string numbers are inferred. Multiple explicit string numbers per timestep are only required when they are not completely consecutive. In general, the number of implicit or explicit strings per timestep must match the number of notes. String numbers are ignored for rests.

This covers the detailed introduction to phrases. The next section will cover related helper functions, some of which have already been seen.